The rise of generative AI is accelerating fundamental changes in how tech companies make their money and calling into question old orthodoxies. Taking a look at the most recent quarterly earnings reports, I highlight some of the limitations of existing ways we typically understand the tech sector and why we should be paying attention to its growing capital expenditure on AI infrastructure.

We may be witnessing an epochal shift in business models as large tech companies change their organisational structure, research priorities and investments to pivot towards AI, which is expected to yield $1.3 trillion in profits by 2032. In what we describe in our book Feeding the Machine as an emerging ‘era of AI’, infrastructure, rather than software, takes on a new critical role.

But first, a word about some of the perspectives through which we often view the political economy of Big Tech. In her 2019 The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff claims to describe the mechanics of a new tech-enabled mutation of capitalism that feeds off individuals’ online activities. The book is pitched as an analysis of a ‘new logic of capitalist accumulation’ and a new ‘frontier of power’.

In reality, it’s a description of a specific business model developed by advertising platforms such as Google and Facebook. These companies offer free digital services in exchange for collecting users’ data which is used to create advertising products sold to third parties. Much of the jargon in the book of ‘prediction products’ and ‘behavioral futures markets’ clouds the central point that these companies’ most profitable operations were simply selling online ads (97.5% of Facebook’s revenue in 2023).

Source: TechTarget. Originally from Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (Public Affairs, 2019).

The surveillance capitalism framework always had its limitations. For one, it had little to say about a host of other tech companies such as Uber, Airbnb and Apple that did not utilise the same advertising model. It also downplayed the extent to which advertising platforms were simply extending existing tendencies within capitalism of commodifying human life for profit. Zuboff wrote as if these tech companies were engaged in some kind of uniquely malevolent and rogue form of capitalism rather than just business-as-usual capitalist accumulation.

Now that the gold rush in generative AI has led large tech companies to invest more into acquiring AI startups and training foundation models which require large capital investments, advertising is no longer the leading edge of capitalist development. Far from surveillance emerging as a new modality of capitalism, some tech companies have diversified their revenue streams. This could be subscriptions, licencing deals, renting ‘AI-as-a-service’, or simply integrating new tools into their existing products.

Of course, selling ads online is still immensely profitable. Alphabet recently posted a large increase in profits from its Search business and Meta is already using AI to optimise their ad business. As Mark Zuckerberg recently announced on an earnings call:

“There are several ways to build a massive business here, including scaling business messaging, introducing ads or paid content into AI interactions, and enabling people to pay to use bigger models and access more compute… and on top of those AI is already helping us improve app engagement, which naturally leads to seeing more ads and improving ads directly to deliver more value.”

But has a focus on the surveillance capitalism model distracted us from other important developments? In the early days of platforms, when we used to speak of a ‘sharing economy’, Nick Srnicek described one of the fundamental features of the platform economy as the presence of ‘lean platforms’: Airbnb doesn’t own any houses; Uber doesn’t own any cars. The value of these businesses was thought to be in the software layer and how they took advantage of ‘network effects’ of large customer bases.

This was also part of a largely ‘immaterial’ understanding of the tech sector based on a vague idea that capitalism had somehow shifted from producing goods and services to dealing primarily with ‘information’ or ‘data’. As McKenzie Wark argued,

‘there is really something qualitatively distinct about the forces of production that eat brains, that produce and instrumentalise and control information.’

From the mid 2010s onwards, what began to shift was the level of capital expenditure on the infrastructural layer of these new technologies: data centres, cloud computing and undersea cables. As AI became the new central focus, Big AI made enormous investments in what we could all AI infrastructure – ‘the computational power and storage needed to train large foundation models’. In 2014, the combined capital expenditure of Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta was less than $5 billion a quarter; in the first quarter of 2024 it was more than $44 billion and has been steadily increasing over the past five years. Microsoft alone increased its capital expenditure by 80% compared to the same time last year.

To understand the sheer scale of investment and the growing concentration of ownership and control, let’s begin with the Internet’s backbone. Undersea cables send 99% of Internet traffic around the world including training data for state-of-the-art AI models. Consortiums of state-owned telecom operators used to own the lion’s share of these cables. However, content providers that accounted for less than 10% of cables prior to 2012 now own more than two thirds, with the largest investments made by Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta. Between 2016 and 2022, large US tech companies invested roughly $2 billion in cables or about 15% of the worldwide total, a figure that over the next three years is likely to increase to $3.9 billion or 35% of the total. This marks a fundamental shift in who owns some of the central digital infrastructure of new technologies.

This increase in spending - and in the concentration of ownership - is also reflected in recent trends in the data centre industry. Investment in the biggest ‘hyperscale’ data centres by the four largest providers was reported to be about $140 billion in 2023, according to Synergy Research Group. This spending is predicted to reach over $200 billion by 2025. The total number of hyperscale centres reached 1,000 in early 2024, with capacity set to double every four years. Over 60% of these centres are owned by the largest three providers: Amazon, Microsoft and Google with the remaining 40% owned by a small number of other large companies.

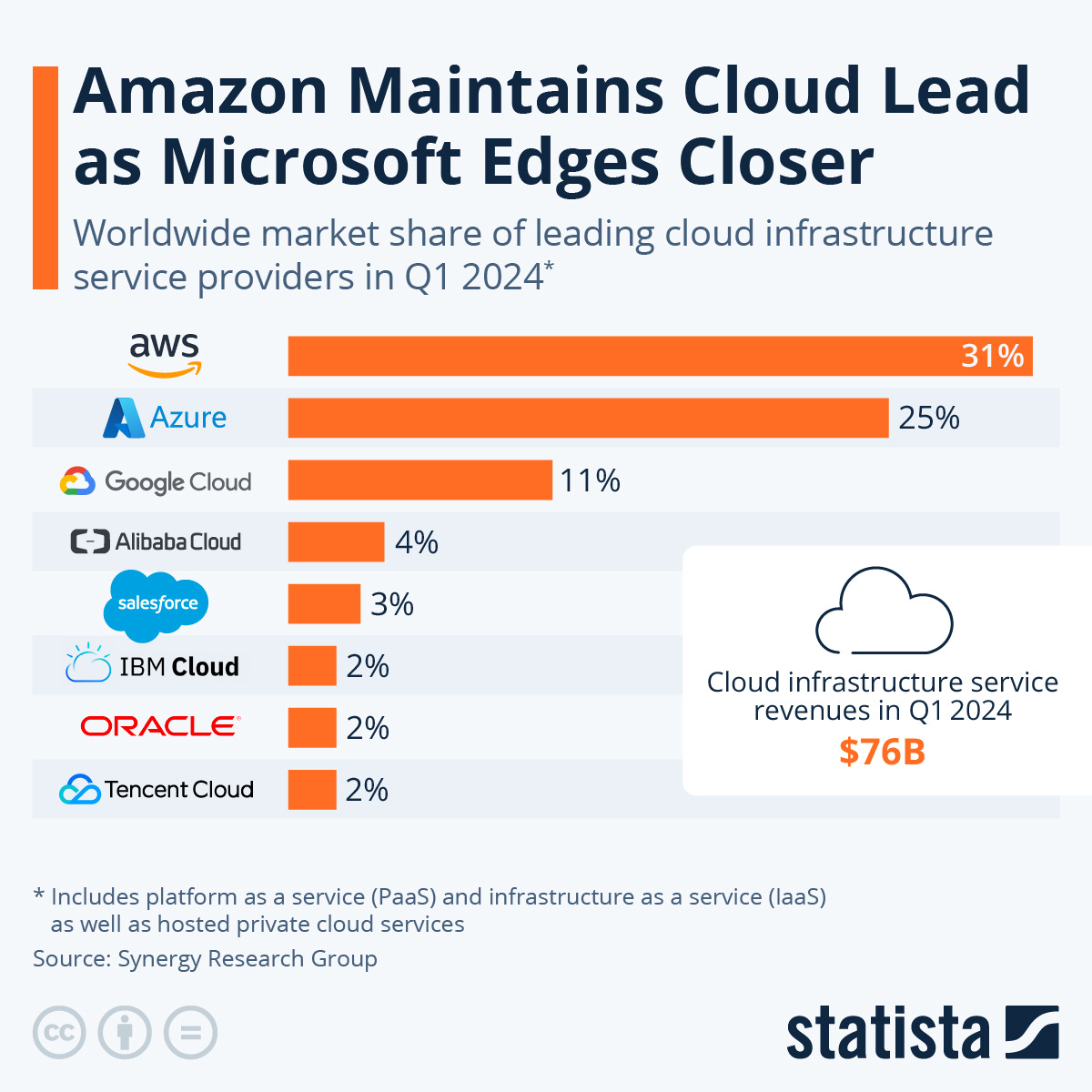

Moving further up the stack, Big AI is also consolidating its dominance over cloud computing infrastructure. The three largest companies - Amazon, Microsoft and Google - account for over two thirds of the $76 billion cloud computing market. The companies recently increased their profits on cloud computing by over 20% year over year compared to Q1 2023.

For the most part, investors are rewarding large tech companies for their increased spending on AI infrastructure, with significant boosts in share prices in Q1 2024 for all of the Big AI firms except for Meta. It is still unclear how quickly AI revenue will flow, but for the time being these massive investments in capital expenditure are being treated as a solid bet on the next big tech boom.

The precise business models that will generate the most revenue are yet to be determined in this new era of AI, but what is clear is that infrastructure is the new kingmaker. In the race for AGI, only a handful of companies own the basic tools to compete. The most recent earnings reports by Big AI companies make clear that this trend will only continue as the major players rush towards further developing their infrastructural power.