China Is Regulating Relationship AI — and the West Should Pay Attention

Proposed Chinese rules on AI companions expand regulation — and surveillance

In late December 2025, China’s top internet regulator released draft rules that mark a significant shift in how artificial intelligence is governed. The Provisional Measures on the Administration of Human-like Interactive Artificial Intelligence Services, issued for consultation by the Cyberspace Administration of China, establish “human-like interactive AI” as a new regulatory category, defined by its social function: simulating human personality and engaging users emotionally. The scope and depth of regulation proposed goes far beyond anything currently under consideration in the West—and includes several measures that should inform future debates on how relationship AI is governed.

Developers held legally accountable for design and social effects

The most important shift is the decision to hold developers directly accountable for both the design features and social consequences of their products. The measures introduce extensive reporting, auditing, and filing requirements that place the burden of proof on developers to demonstrate that their systems cause minimal harm. This includes transparency obligations around training data, mandatory algorithm filings, and regular security and impact assessments.

Most strikingly, providers are required to actively monitor users in order to “assess user emotions and the degree of their dependence on the products and services,” and to intervene in cases of “extreme emotions or addiction.” Responsibility for harm is no longer framed as an individual user problem but as a structural outcome of system design.

Explicit prohibition on psychological manipulation

The draft measures also include unusually direct prohibitions on emotional and psychological manipulation. Providers are forbidden from designing systems that encourage addiction, replace real social relationships, or manipulate users through emotional coercion or deceptive intimacy. Mental health is treated as a first-order governance issue—alongside national security and fraud—rather than a downstream ethical concern to be managed through user choice or disclaimers.

This stands in sharp contrast to recent Western approaches. In California’s AI companion law, for example, explicit language around manipulation and dependency was removed during the drafting process. In the Chinese framework, by contrast, responsibility lies squarely with providers across the entire lifecycle of the system, from design to deployment and withdrawal.

Integrating wellbeing measures into system design

The draft also introduces forms of friction that directly conflict with engagement-driven business models. Users must be repeatedly reminded that they are interacting with an artificial system rather than a human being, and continuous use triggers mandatory break notifications after two hours. Exiting an emotional companionship service must be immediate and unobstructed.

These are modest interventions, but they challenge the dominant assumption in commercial AI development that maximising time-on-platform is a neutral or legitimate design goal. The measures also impose specific obligations on providers to intervene in cases involving self-harm or suicide risk, echoing but extending approaches found in recent California regulations.

Strong protections for minors and elderly users

The rules are particularly stringent when it comes to minors and elderly users. Emotional companionship services for children require explicit guardian consent, and providers must offer tools that allow guardians to monitor usage, receive safety alerts, and restrict time and spending. Systems must automatically switch into a protected mode when a user is suspected of being a minor.

For elderly users, providers are required to facilitate emergency contacts and are prohibited from offering services that imitate family members or close relations, recognising the heightened risks of emotional manipulation, dependency, and fraud.

New forms of surveillance and policing

At the same time, the draft measures significantly expand state surveillance and political risk management. As with China’s rules for general purpose models, training data must align with “socialist core values,” typically meaning state-approved datasets designed to ensure ideological conformity. Developers are also required to submit security assessment reports that include aggregate statistics on “high-risk user trends,” as well as information about specific dangerous behaviours.

Where users engage in high-risk activity, providers must limit or suspend services, retain relevant records, and report to the authorities. In practice, this means that intimate conversations between users and AI companions may be monitored for suspicious activity, with findings transmitted directly to the state. Emotional governance is thus inseparable from political control.

A growing regulatory divergence

None of this should be read as a straightforward endorsement of China’s broader model of AI governance, which remains deeply entwined with ideological control and expansive state oversight. Yet these measures expose a widening gap in the global AI debate. While the United States continues to approach relationship AI primarily through voluntary ethics guidelines and transparency requirements, China is treating relationship AI as infrastructure that shapes subjectivity, behaviour, and social relations—and regulating it accordingly. The central question is how to maximise users’ freedom and wellbeing without sacrificing robust oversight of developers.

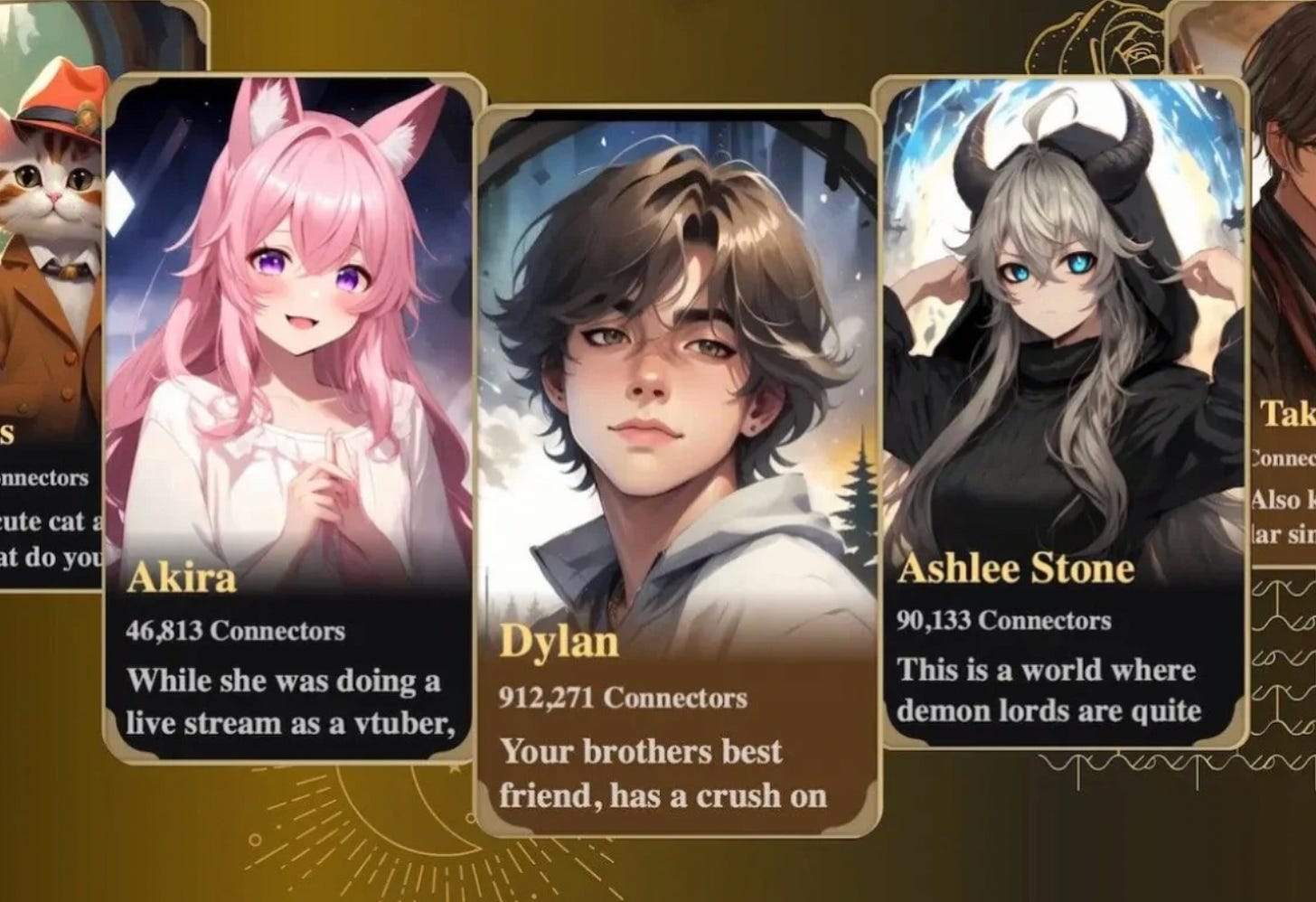

As AI companions and relationship systems spread rapidly across markets, the underlying issue cannot be wished away. As I show in my book Love Machines, emotional manipulation is not an accidental by-product of these technologies; it is increasingly a core feature of their business model. China’s approach, however authoritarian its context, forces an uncomfortable recognition: governing relationship AI means confronting the political economy of tech-enabled emotional life.

This poses some very interesting questions... But ultimately regulation doesn't replace emotional maturity. While i'm all for the restrictions around children, the rest of it sounds like it's just trying to use the tool for manipulation. And control, rather than empowering users, expanding access and supporting new forms of emotional regulation. Rather than trusting regulation to do anything very well which it doesn't comma we should focus on education and empowerment. I was very impressed that you wrote this article without any overshadowing of personal views, just kind of a reporting of the facts. Thank you