Seven Theses from Feeding the Machine

New Book – Publication 18 July 2024 (UK) / 6 August 2024 (US)

Hi everyone

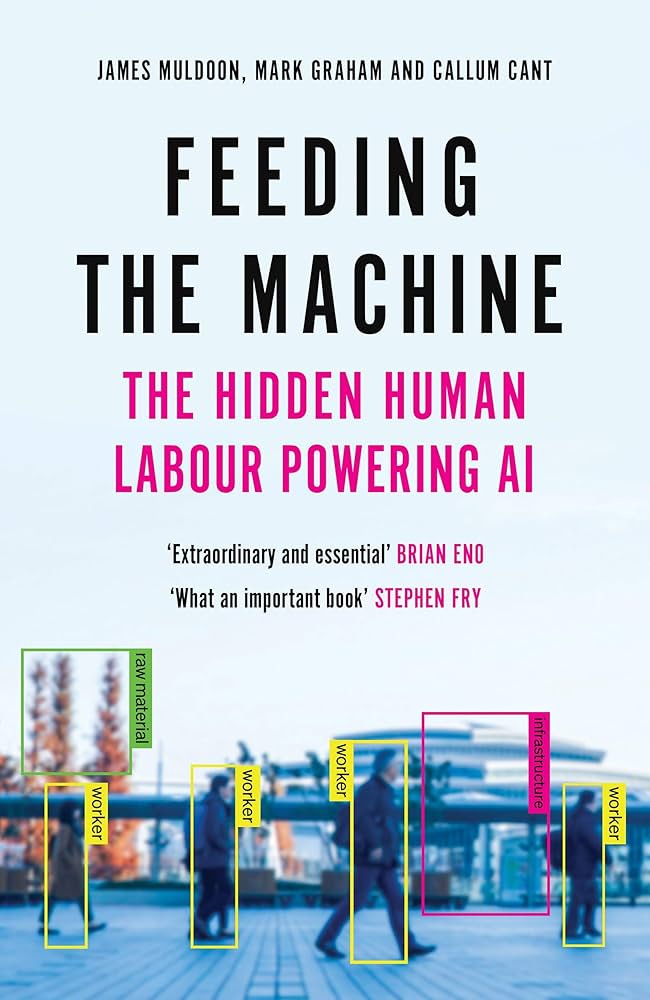

I haven’t been able to post for a while because I’ve been moving house, but yesterday an extract and interview from my new book, Feeding the Machine was published in the Observer/Guardian. I thought I would link it here with a brief overview of some of the book's central ideas.

Here is the interview with Ian Tucker and a short extract featuring Mercy and Anita, Kenyan and Ugandan AI data workers whose stories we cover in our book.

With the book to be released on 18 July 2024 in the UK and 6 August 2024 in the US, I thought I would highlight some key takeaway points.

AI requires a hidden army of workers often working in terrible conditions

Behind the smooth surfaces of our tech products lies the physical labour of millions of workers across the globe. Feeding the Machine is about the hidden human cost of the AI revolution. It’s a story of the rise of AI told from the perspective of the workers who build it. 80% of the work of AI is not done in AI labs by machine learning engineers; it’s data annotation work that is outsourced to workers in the Global South. The stories we heard when we visited what could be described as digital sweatshops were horrendous: endless days of tedious work on insecure contracts earning little more than $1 an hour with no career prospects. When we buy other consumer products like coffee or chocolate, many of us are aware of the supply chains and manual labour that make this possible. This is not always the case for digital products. But we are directly connected with these workers dispersed across the globe and actions we take as consumers, workers and citizens can make a big difference to their lives.

AI supply chains reflect older colonial patterns of power that still shape modern technologies

In many ways, the book is also a story of the afterlives of the British Empire and the colonial histories that influence how AI systems are produced today. There’s a reason why this work is outsourced to workers in former colonies. They are countries that have experienced harsh histories at the hands of European colonial powers and tend to suffer from underdevelopment and a lack of job opportunities as a result. Western AI companies take advantage of the relative powerlessness of workers in these countries to extract cheap and disciplined labour to build their products. There is more than just an echo of colonialism in AI – it’s part of its very DNA. AI is produced through an international division of digital labour whereby coordination and marketing is directed by executives in the US while precarious and low-paid work is exported to workers in the Global South. Minerals needed to produce AI infrastructure are also largely mined and processed in former colonial countries. The outputs from generative AI also privilege Western forms of knowledge and reproduce damaging stereotypes and biases found in AI’s datasets.

AI is an ‘extraction machine’ – it feeds off our physical and intellectual work

We often hear stories of AI as a replica or mirror of human intelligence – an attempt to reproduce the basic structure of intelligent thought in a machine. But from the perspective of workers and consumers, it is more accurate to understand AI as an ‘extraction machine’: a system that feeds off the physical and intellectual labour of human beings to produce profits for Big Tech companies. We argue that the logic of this machine is to extract the inputs of human labour, intelligence, natural resources and capital and convert these into statistical predictions for new tech products. Understanding AI using this machinic metaphor reminds us that as a machine AI has its own history, politics and power structures. A machine is not objective or neutral; it’s built by specific people to perform particular tasks. When it comes to AI, the extraction machine is an expression of the interests of wealthy tech investors and is designed to further entrench their position and concentrate their power.

Generative AI is theft

AI requires the manual labour of data annotators and content moderators, but it’s also based on what we call ‘the privatisation of collective intelligence’. The value of generative AI tools is based on original human creative work that has been ripped off and monetised. All of the books, paintings, articles and recordings used to train generative AI models are largely unacknowledged and unremunerated. No consideration has been given to the human creatives whose work is used to create knock-offs and competitors in the creative market. In the book, we tell the story of an Irish voice actor who finds a synthetic clone of her own voice online, one that has been created without her knowledge and which poses a completely novel threat to her livelihood. Companies have been devaluing the work of artists for generations and many imposters have been trying to make fakes and derivatives. But AI raises the stakes and allows for this to be done with greater ease and at a larger scale than ever before. Generative AI tools enable tech companies to rob an entire creative community of their value and talent, with little to no protection from existing laws.

The commercialisation of AI is leading to a new conglomerate of “Big AI” firms which concentrates power in fewer hands

We need to start talking not just about, “Big Tech”, but “Big AI”. The commercialisation of AI is leading to a further concentration of power in large American tech companies. If you look at the major investors in younger AI startups they are legacy tech companies who want to be seen as leaders in the AI race. This is going to reduce competition in the sector and monopolise decision making power in the hands of a tiny class of Silicon Valley elites. Big AI firms include leading cloud computing providers such as Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet, in addition to AI startups like OpenAI, Anthropic and Mistral, alongside chipmakers such as Nvidia and TSMC. These companies tend to understand AI as a commercial product, one that should be kept secret and used to make profits for investors. OpenAI was started with the goal of developing general artificial intelligence for the good of humanity, but we are increasingly seeing how farcical this is: billions of investment from Microsoft, working with the US military, training data on copyrighted works, imitating Scarlett Johansson’s voice without her consent. There are only a few companies that have the infrastructural power to train foundation AI models and it is these that will benefit the most from the AI revolution.

Generative AI is a catastrophic disaster for the environment

In 2019-2020, all of the leading tech companies promised to make dramatic cuts in their emission, with the goal of being carbon neutral or negative by 2030. Five years on and these pledges are looking increasingly hollow. Microsoft’s emissions have increased by 30% and Google’s have increased by almost 50% as a surge in AI has rapidly increased investment in data centres resulting in a growth in greenhouse gas emissions. This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Global data centre electricity demand is set to double by 2026. One large data centre consumes as much electricity as 80,000 US households. Cloud computing has a larger emissions profile than the entire airline industry. And it’s the same problem with water: a large data centre can consume roughly between 10 and 20 million litres of water each day, the same as an American town of 50,000 people. Initiatives that put AI in the service of reducing emissions are unlikely to offset this problem as they must also be considered alongside the oil and gas companies that will use AI to extract more fossil fuel.

The only way to change things is through collective political action, primarily by workers and civil society.

Change will only come about when we work together to force these tech companies to change their practices. We see time and again throughout history that powerful social groups do not give up their position unless they are directly challenged through political struggle. The number one strategy we advocate in the book is for people to come together through workers’ and civil society organisations to build collective power and put pressure on tech companies to provide better conditions and improve the lives of their workers. There are many things we can all do to contribute to this struggle, but it’s through working together and supporting the struggles of workers in these AI supply chains that we can hope to make the biggest difference. Real social transformation is most likely to occur through a fundamental shift in the balance of power between social groups. While there are specific policies and proposal we discuss in the book, we want to leave readers with the main point that the issue is primarily a product of the disproportionate power enjoyed by large tech companies and that workers must build their own power to oppose this. It’s only by reimagining how AI is produced in this way that we can turn it into a more emancipatory technology in the service of humanity.